Phishing has changed a lot in recent years. What used to be simple, poorly written emails is now often a planned, multi-step attack. Modern phishing follows clear patterns and well-defined processes. Attackers prepare carefully. They study organizations, use public information, and adapt their messages to normal business situations. Their goal is to look harmless and routine, not suspicious.

To understand this threat, it is not enough to look at single emails or blame human error. Phishing must be seen as a full attack process — from target selection to technical preparation and exploitation. This article explains the seven key phases of a modern phishing attack. It aims to make the structure visible and support realistic, informed security decisions.

Phase 1: Reconnaissance and Target Selection

Before a single phishing email is ever sent, the real work begins: reconnaissance. Modern attackers do not rely on chance. They use systematic information gathering to select and profile their targets with care and intention.

In this phase, cybercriminals leverage open-source intelligence (OSINT) to collect information from a wide range of publicly accessible sources. These include professional networks such as LinkedIn, corporate websites, press releases, social media platforms, and public databases. The goal is to understand not only who works at an organization, but how the organization functions.

Attackers identify employees in key roles—such as finance, HR, IT, or executive support—who are more likely to receive or process sensitive requests. They map organizational structures, reporting lines, and typical communication patterns. Email formats, tone of voice, naming conventions, and commonly used tools all become valuable data points.

The depth of this research is directly related to the potential payoff. For broad, opportunistic phishing campaigns, reconnaissance may be minimal. For targeted spear-phishing attacks, however, this phase can last days or even weeks. During this time, attackers collect contextual details such as:

-

ongoing projects or deadlines

-

recent organizational changes

-

vacation periods or out-of-office patterns

-

business partners, suppliers, and recurring workflows

All of this information is later used to craft convincing pretexts that feel authentic and contextually accurate. When the phishing message eventually arrives, it does not appear random or suspicious—it appears timely, relevant, and expected.

Phase 2: Modern phishing pretexts

Once a target has been selected, attackers move on to one of the most decisive stages of a phishing attack: pretext design. The pretext is the story that gives the message meaning and credibility. It defines why the recipient should open an email, click a link, or respond—without ever questioning the action.

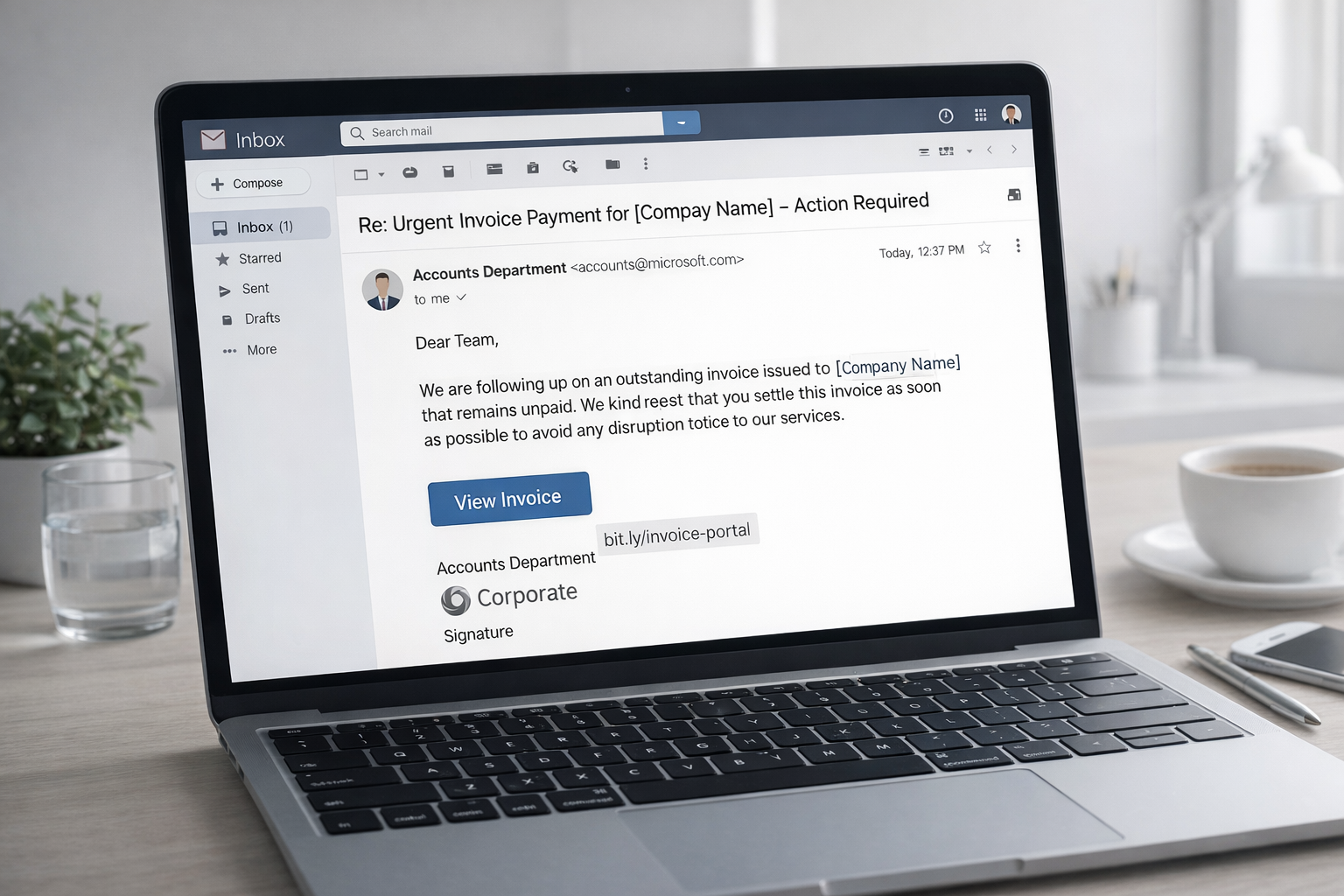

Modern phishing pretexts are carefully chosen to align with everyday business routines. They are rarely sensational or dramatic. Instead, they revolve around familiar scenarios such as updated invoices, shared documents, contract adjustments, or routine security notifications. These themes are deliberately mundane, because familiarity lowers resistance. When a message resembles something the recipient sees every week, it blends seamlessly into normal workflows.

The primary objective at this stage is not urgency alone, although time pressure is often used as a secondary element. The real goal is plausibility. The message must feel expected. It should match the recipient’s role, current responsibilities, and typical communication patterns. A finance employee receives a billing-related request. An executive assistant sees a calendar or document update. An IT-related message is framed as a routine system notification.

To achieve this, attackers incorporate details gathered during reconnaissance. They mirror internal language, use correct terminology, reference real colleagues, partners, or service providers, and align the message with ongoing business activities. Even subtle details—such as writing style, tone, or formatting—are adapted to match what the recipient is accustomed to seeing.

Well-designed phishing emails therefore do not rely on obvious red flags. They avoid spelling mistakes, exaggerated threats, or unusual demands. Instead, they create a sense of normality. The recipient does not feel alarmed or suspicious; they feel efficient, responsive, and helpful—simply doing their job.

This is what makes pretext design so effective. A good phishing message does not feel like an attack. It feels like just another task in a busy workday.

Phase 3: Infrastructure Preparation

While the phishing message itself is often the most visible part of an attack, it is only effective because of the technical infrastructure prepared in advance. Before any email is delivered, attackers set up the systems that will support the deception and enable the next stages of the attack.

This preparation typically begins with the creation of look-alike domains that closely resemble legitimate services or internal company resources. Small variations in spelling, characters, or domain endings are used to make these addresses appear trustworthy at a glance. The goal is not to withstand careful inspection, but to pass unnoticed during routine interactions.

Attackers then deploy cloned websites or login pages, often modeled after widely used platforms such as Microsoft 365, Google Workspace, or internal portals. These pages are designed to look and behave like the originals, including logos, layouts, and login prompts. To further reinforce legitimacy, attackers commonly implement HTTPS encryption and valid certificates. For many users, the presence of a secure connection falsely signals safety.

The underlying infrastructure is deliberately lightweight and short-lived. Hosting providers, cloud services, or compromised systems are used to spin up environments that can be abandoned quickly. If a phishing domain is blocked or reported, it is simply replaced. This flexibility allows attackers to stay ahead of blacklists and automated detection mechanisms.

In more advanced campaigns, infrastructure preparation may also include email forwarding mechanisms, credential collection scripts, or automated access testing tools. These components ensure that once credentials are entered, they can be validated and exploited with minimal delay.

From the defender’s perspective, this phase is particularly challenging because it unfolds entirely outside the organization’s perimeter. No internal systems are accessed yet, no alerts are triggered, and no users are involved. Nevertheless, critical groundwork is being laid.

Phase 4: Delivery (The Initial Contact)

With the pretext defined and the technical infrastructure in place, the attack reaches its first visible stage: delivery. This is the moment when the phishing message is sent and enters the target’s environment. Despite its apparent simplicity, this phase is carefully timed and strategically executed.

Email remains the most common delivery channel, but modern phishing campaigns increasingly make use of alternative vectors such as SMS messages, collaboration platforms, calendar invitations, or messaging services. The choice of channel depends on the target, the context, and the likelihood that the message will be perceived as legitimate.

Timing plays a critical role. Attackers often send phishing messages during periods of high cognitive load—early in the morning, shortly before meetings, at the end of the workday, or during busy reporting cycles. At these moments, recipients are more likely to act quickly and rely on routine rather than careful verification.

The message itself is usually concise and purpose-driven. It does not ask the recipient to think, investigate, or decide. Instead, it presents a task that fits naturally into existing workflows: reviewing a document, confirming a change, or addressing a minor issue. The design is intentional. The less attention a message demands, the more likely it is to be acted upon without resistance.

Importantly, delivery does not aim to overwhelm security systems. Many phishing emails are technically unremarkable. They avoid suspicious attachments, excessive links, or aggressive language that might trigger automated filters. Instead, they are engineered to pass through defenses by appearing ordinary and compliant with everyday business communication standards.

At this stage, the attack still depends entirely on perception. Nothing has been compromised yet. No credentials have been stolen. No systems have been accessed. And yet, a single message—properly timed and contextually aligned—can be enough to move the attack forward.

Phase 5: Interaction and Credential Capture

Phase 5 begins the moment a recipient interacts with the phishing message. This interaction may seem insignificant—a click on a link, the opening of an attachment, or the approval of a request—but it marks the transition from preparation to active compromise.

In many modern phishing attacks, the interaction leads the user to a deceptive login page that closely resembles a legitimate service. These pages are often indistinguishable from the originals at a visual level. Logos, layout, language, and even security indicators such as HTTPS are carefully replicated to maintain trust. From the user’s perspective, this appears to be a routine authentication step.

When credentials are entered, they are captured in real time. In some cases, the victim is redirected to the legitimate service immediately afterward, reinforcing the impression that nothing unusual has occurred. The login “worked,” the task is completed, and the incident is mentally closed.

Other variants rely on document-based interaction. Attachments may request macro activation, prompt additional downloads, or trigger background processes that establish persistence. More advanced campaigns exploit OAuth consent mechanisms or harvest session tokens, allowing attackers to bypass traditional authentication controls entirely.

What makes this phase particularly dangerous is its lack of visible impact. There is no system crash, no error message, and no immediate disruption. The user experiences a normal outcome and moves on. Meanwhile, attackers quietly validate the captured access and prepare for the next stage.

At this point, the attack has succeeded in its primary objective: gaining a foothold. Everything that follows—data access, internal movement, financial abuse—becomes possible because this interaction appeared routine and harmless.

Phase 6: Access Validation and Lateral Movement

After credentials or access tokens have been captured, attackers do not immediately act in obvious ways. Instead, they begin by validating and stabilizing their access. This phase is deliberately quiet. Its purpose is to confirm that the obtained credentials work as intended and to assess how far the access can be expanded without raising suspicion.

Attackers typically log in from a different location or device, often using anonymization techniques to blend into normal traffic patterns. They test whether multi-factor authentication is enforced, whether session tokens remain valid, and whether conditional access policies are in place. In many cases, stolen session tokens allow attackers to bypass MFA entirely, making the login appear legitimate to security systems.

Once access is confirmed, attackers explore the environment. Email inboxes are reviewed for ongoing conversations, financial processes, and internal communications. Password reset messages, security alerts, and approval workflows are of particular interest. Some attackers create inbox rules or forwarding mechanisms to silently monitor communications without interrupting the user.

From there, lateral movement begins. Attackers look for additional accounts, shared resources, cloud services, or administrative portals that can be accessed with the compromised identity. The goal is not speed, but persistence and coverage. Each new access point reduces the likelihood that a single account reset will end the intrusion.

This phase often remains undetected for extended periods. Because attackers use valid credentials and standard interfaces, their actions blend into normal user behavior. Security teams may see logins, but nothing that clearly indicates malicious intent. Meanwhile, the attacker gains a deep understanding of internal processes and identifies opportunities for exploitation.

By the time suspicious activity is noticed, the original phishing email is often long forgotten. The incident appears to emerge suddenly, even though the groundwork was laid quietly days or weeks earlier.

Phase 7: Exploitation and Monetization

Once attackers have established stable access and gained sufficient insight into the environment, the attack enters its final phase: exploitation and monetization. At this point, the original phishing message has fully served its purpose. What follows depends on the attacker’s objective, but the underlying principle is the same: turning access into value.

In many cases, this phase begins with financial exploitation. Attackers manipulate payment workflows, alter invoices, or intercept ongoing financial communications. Because they understand internal processes and timing, fraudulent requests often appear legitimate and are processed without hesitation. Business Email Compromise (BEC) schemes frequently unfold at this stage, sometimes resulting in substantial financial losses within hours.

Other campaigns focus on data access and extraction. Sensitive documents, customer records, intellectual property, or internal correspondence may be collected quietly over time. In some cases, this data is used directly for extortion. In others, access is sold or transferred to additional threat actors, extending the lifecycle of the incident beyond the original attack.

In more disruptive scenarios, exploitation leads to ransomware deployment or system sabotage. Because attackers already understand the environment, they can choose the most damaging moment to act—often outside of business hours or during critical operational periods. At this point, recovery becomes complex and costly, even if the initial phishing email appeared harmless.

What makes this phase particularly challenging is that it often appears sudden and disconnected from its origin. Organizations may perceive the incident as an unexpected breach or system failure, while the true entry point lies weeks in the past. The phishing email itself is no longer visible, but its consequences are now unavoidable.

Conclusion: Phishing Attack Phases Explained

Phishing attacks are not random events. They follow clear phases that build on each other over time. When these phases are understood as one connected process, phishing becomes easier to detect and stop.

Each phase offers a chance to interrupt the attack — through better awareness, stronger controls, and smarter monitoring. Most successful attacks do not happen because of one big mistake, but because several small gaps are missed.

For businesses, effective protection means more than email filters or basic training. It requires understanding how phishing works as a system and aligning security measures with real attack patterns.

Phishing will continue to change, but its structure stays the same. Once this structure is understood, phishing becomes less complex and much more manageable.

I recommend you to read the follow articels

Can a PDF File Be Malware? The Hidden Dangers You Need to Know

Examples of Phishing Attacks on Small Businesses — And How to Detect Them Early

Exposing phishing emails: How to recognize fraud attempts – safely and systematically

Learn, understand, and stay prepared

Join my Slack channel for clear, real-world cybersecurity guidance.

Or subscribe to my newsletter and receive the first three chapters of Behind the Backdoor with the first email.